This essay is an attempt to illustrate the gendered notion of Indianness with reference to certain Hindi films. This essay will explore the portrayal of women in cinema from the early 1930s to the 1950s and analyze the changes that took place post-Independence. It will analyze one of the most globally recognized Indian films of all time, Mother India, and its notions of what it means to be an Indian man and woman. Finally, it will look at a couple of contemporary films and analyze gendered Indianness through its lenses.

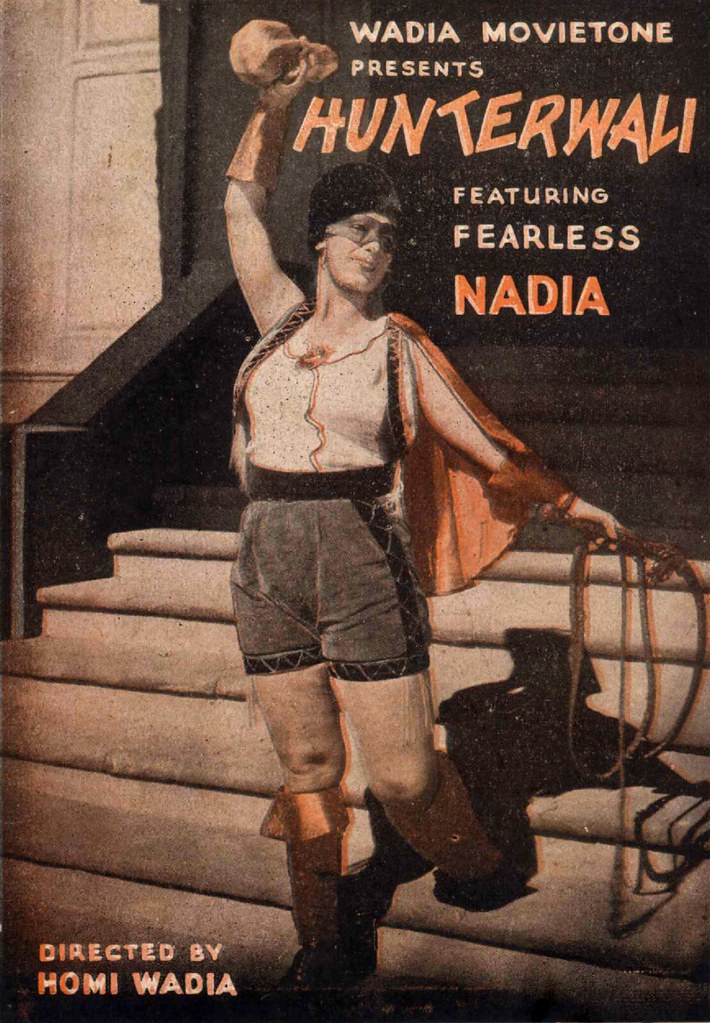

Prior to independence, movies portraying female sexuality and autonomy were common. In Aadmi, a dancing girl kills her evil uncle and prefers to stay in prison than accept her beloved’s help. In Duniya Na Maane, the female lead refuses to consummate her marriage with a much older man. And in Hunterwali and Miss Frontier Mail, we see perhaps the only ‘action woman’, Fearless Nadia, gracing the silver screen. Therefore, prior to independence, there wasn’t an extremely robust gendered framework of what it meant to be Indian. It can even be argued that the ‘Indian’ at that time was one who overcame stereotypes and societal expectations to commit heroic acts for the greater good, regardless of gender.

This changed significantly post-Independence. The set up of Raj Kapoor’s RK Films and Dev Anand’s Navketan Films diverted cinematic themes towards male-centric ones. Progressive, idealistic women were increasingly being replaced by the traditional and submissive. India was going through an extremely difficult period post-Independence trying to carve an identity out of itself after centuries of colonialism. And in its quest to discover what Indianness truly meant, it resorted to gendered ideas of what an ideal Indian man and Indian women represented. The Indian woman was chaste, pure and fiercely protective of her family. She placed her husband and her children’s wellbeing above that of her own. The Indian man, in contrast, was in the process of trying to shed its effeminate characterization and take on more masculine, stoic and violent traits.

Mehboob Khan’s film, Mother India is a significant milestone not only in Bollywood cinema but post-Independence Indian history as well. The film, a namesake of Katherine Mayo’s racist account of Indian unfitness to self-govern and a propagandistic portrayal of India’s sexuality, misogyny, culture, and poverty, took on a monumental challenge of redefining what it meant to be Indian. The lead protagonist, Radha, is supposed to be the embodiment of the Indian nation itself. She is also supposed to be the epitome of what an Indian woman should be. Radha continues to provide for her children even when her husband abandons her. She preserves her chastity by refusing to sleep with the moneylender; even if that meant alleviation of all her financial troubles. Finally, she shoots her own son for the greater good. We, therefore, see the genesis of the ideas of chastity, sacrifice and family being associated with the woman.

Mother India also makes allusions to what it means to be an Indian man. While the Indian woman nurtures the family, the Indian man must always be in a position to provide for it. When Radha’s husband handicaps himself, he loses his identity of what it means to be a man. Overcome by the guilt of not being able to support his family financially, he chooses to abandon them and commit societal suicide.

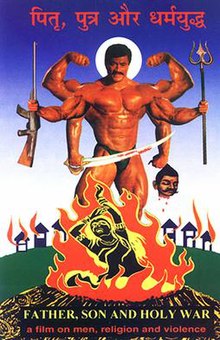

The documentary film Father, Son and Holy War showed the extremely problematic rise of toxic masculinity in India. The documentary claimed that the Hindu man was on a quest to shed its British Raj stereotype of effeminacy and look to militant mythological figures such as Ram and Shiva. Therefore, one of the prime drivers of the Indianness for a man was to preserve his mardangi. This meant keeping the wife in check, waging war against those that threatened their way of life, resorting to banned practices (such as sati) to re-establish male dominance and using misogynistic, effeminate language to describe those that they perceived as ‘the enemy’. For the Indian man, there couldn’t be a bigger shame than being referred to as a eunuch.

In tandem, the woman became the property of her husband. She was expected to be the embodiment of Indian tradition and culture, a personification of the goddesses Sita and Parvati. Her loss of chastity essentially meant the loss of her dignity and life. An unchaste woman was as good as dead. Therefore, what started off as an exercise to rebrand India became dangerously misogynistic, threatening the lives of millions of women nationwide.

The bleakness of the patriarchal notion of Indianness is perhaps best portrayed in the movie Fire. One of the central themes of Fire is sexuality. The film portrays two deeply troubled marriages. The husbands, however, satiate their sexual desires through prostitutes and masturbating to pornography. The wives, in stark contrast, are expected to repress their sexuality if their husbands are not able to satiate it. In their sheer desperation, the women resort to each other to feel tenderness and affection. Their act is considered sacrilegious and an affront to female chastity and purity. The film, therefore, is a comment on the expectations of sexuality. The Indian man is allowed to explore it in any way possible. The woman, on the other hand, can do so only in association with the husband.

Films are perhaps the most potent tools to analyze the expectations and beliefs of its producers and audience. Since the inception of cinema, films have resorted to challenge or affirm the severely gendered notions of Indianness. However, one fact is supported by all; it is that what it means to be Indian starkly differs for a man and a woman. The woman is chaste, pure, repressed, traditional and sacrificial. The man is the provider; violent in his wars and stoic in his pain.

Bibliography

- Somaaya, B., Kothari, J., & Madangarli, S. (2012). Mother maiden mistress: Women in Hindi cinema, 1950-2010. New Delhi: HarperCollins India, a joint venture with the India Today Group.

- Thomas, R. (1989). Sanctity and scandal: The mythologization of mother India. Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 11(3), 11-30. doi:10.1080/10509208909361312

- Fire, Sparks and Smouldering Ashes | Bina Fernandez … (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/4083247/Fire_Sparks_and_Smouldering_Ashes

- Lutgendorf, P. (2007). Is There an Indian Way of Filmmaking? International Journal of Hindu Studies, 10(3), 227-256. doi:10.1007/s11407-007-9031-y

Filmography

- Khan, M. (1957). Mother India. Mumbai.

- Patwardhan, A. (1995). Father, Son, and Holy War. Mumbai

- Mehta, D. (1998). Fire. Mumbai