Disclaimer: This post is part of a series of essays I wrote at the Young India Fellowship. This particular essay was written as part of the Critical Writing course on Mind, Society and Behavior.

In the World Development Report 2015- Mind, Society and Behavior published by the World Bank Group, the team of authors led by Karla Hoff and Varun Gauri try to establish the incredible need of governments and policymakers to be aware of human irrationality and using this understanding to develop better policies. In the first chapter, entitled ‘Thinking Automatically’, the report states that there are two principal systems of thinking: automatic and deliberative. Next, supported by evidence from various studies, they try to show how the automatic system is responsible for making the bulk of our decisions despite being extremely error prone and biased. Finally, the chapter seeks to explain the various predictable cognitive biases that our automatic systems are prone to and how to use these biases to frame and design better choice architectures that could nudge people towards making better decisions.

The chapter begins by noting the seminal works of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky which led to the foundation of the field of Behavioral Economics and the understanding that humans don’t always evaluate all information and choices equally before making their decisions; a central assumption of the Standard Economic Theory. Although such a deliberative system does exist, it is extremely slow and resources hungry. Therefore, humans prefer employing a faster, although the error-prone, automatic system of thinking that generates simpler models using limited information and leads to faster decision making.

The chapter then goes to explain various biases in assessing information that arises on account of using the faster, automatic system. The first is framing, where individuals tend to give more weight to information that is of little or no relevance. Governments are aware of this particular kind of irrationality and there are examples that exist that show them actively trying to counter it (For example, the ban on leading questions in a court of law). It is indeed possible to use framing to counter climate change behavior among individuals. Running advertisements and posting billboards detailing graphic damages caused to individuals will go a long way in sensitizing people about the magnitude of the problem.

The second effect is that of anchoring where the automatic system tends to cling on to a piece of irrelevant information in order to interpret a choice context; sometimes extremely erroneously. Examples of this include the tendency of people to bargain to reduce the price of an auto ride by 10 rupees but forego similar bargaining activity of even the order of, say a thousand rupees, when buying a car worth more than a lakh.

The anchoring bias also sheds light on something called the ‘peanuts effect’ wherein people tend to ignore the consequences of small monetary transactions as they are viewed as being worth ‘peanuts’ or effectively nothing. However, when added up, these ‘peanuts’ become of immense value and could lead to non-trivial benefits if they were not ignored in the first place. This particular effect is of great significance to climate change policies as well. When individuals pollute the environment, they rationalize their actions by telling themselves that their small act is ‘peanuts’ or of little significance to the magnitude of the total pollution in the environment. Therefore, it is important that people be made aware of the total mess they create, on average, in a year as a result of ignoring these small but numerous acts.

The next section of the chapter focused on biases that arose on account of assessing value. The two primary effects described were the potency of default options and the phenomenon of loss aversion. In the former, people are extremely prone to taking the default option presented by their choice architecture. A study in the United States found that the number of colleges that high school students applied to increased from three to four when the number of free test score reports increased by the same value. Such a minute change, the report demonstrated, had extremely far-reaching consequences.

In the context of air pollution, this effect has potentially far-reaching consequences. The objective of a policy must be to present default options that are environmentally friendly and introduce greater inertia in switching. For instance, making public transportation cheaper, comfortable and more readily available will lead people to make it their default, more convenient choice over personal transportation. Similarly, introducing a ‘firecracker permit’ for consumers will severely deter them from applying for such a permit and in the process, buying firecrackers too.

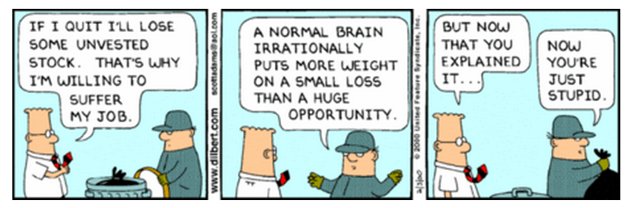

The phenomenon of loss aversion is rooted in the idea that people are more averse to losses than they are to gains of similar magnitude. This effect has been observed and studied in various circumstances such as improving the performance of school teachers and their classrooms. Although the proponents of nudge strongly believe that their methods are ethical and do not interfere with free will, loss aversion policies prove to be an exception. Loss aversion tends to be principally rooted in fear and manipulating people’s fears to achieve results, no matter how beneficial they are, is an inherently unethical thing to do. That being said, policies rooted in this bias may prove to be immensely effective. During festivals such as Diwali, the lower income groups tend to burst a disproportionately larger number of firecrackers. It is, therefore, possible to introduce a policy where the Government provides a ‘gift’ to everyone in the lower income group but with the condition that they stand to lose their claim if they burst firecrackers or obtain a permit as explained earlier.

The final sections of the chapter explain the intention-action divide wherein individuals, despite being in possession of complete information and knowledge of the right action, tend to act in a manner that is counter-intuitive. Various policies such as SMS Reminders and Cash Awards in a variety of fields have proven to be effective in bridging the intention-action gap. In the context of air pollution in Delhi, it would be extremely useful to apply the aforementioned principles in deterring farmers from burning their crops just after harvest.

People tend to think automatically and in the process, employ biases and make suboptimal decisions. This review carefully analyzed the various biases and their natures and how they can be used to effectively combat the pollution in a high-risk city such as New Delhi. The Government must make it a point to dispel the peanuts effect and educate how small actions lead to extremely large consequences. It could also introduce banners and ads that explicitly describe what air pollution can do to their health. Its policies regarding environmentally harmful products must always be attached to providing better options to the point where it becomes the default and introducing inertia and artificial supply shortages to environmentally problematic ones. It could also look into policies that offer conditional rewards and exploit the effect of loss aversion. Finally, it can take steps to bridge the gap between intention and action by notifying perpetrators (such as crop burners) of their harmful activities on time.