Disclaimer: This post is part of a series of essays I wrote at the Young India Fellowship. This particular essay was written as part of the Critical Writing course on Mind, Society and Behavior.

I believe the summer of 2016 was one of the most significant phases of my life. I had slipped into a period of depression and my personal and academic life was suffering immensely as a consequence. At my lowest point, I had turned to literature. It seemed to me to be my last respite; my messiah. And it did not disappoint. In a span of three months, I had read close to 75 books. There were days where I was completing 500 pages in a single sitting. I do not know if there is an upper threshold at which reading could be considered unhealthy but if there is, I am pretty sure I had far surpassed that limit.

I can say with absolute confidence that I learned more about myself and the world around me in those three months than the time encompassing the rest of my existence. Therefore, what I reflect upon in this essay will draw heavily from my readings (of philosophy, fiction, science, and religion) from the summer of 2016;.

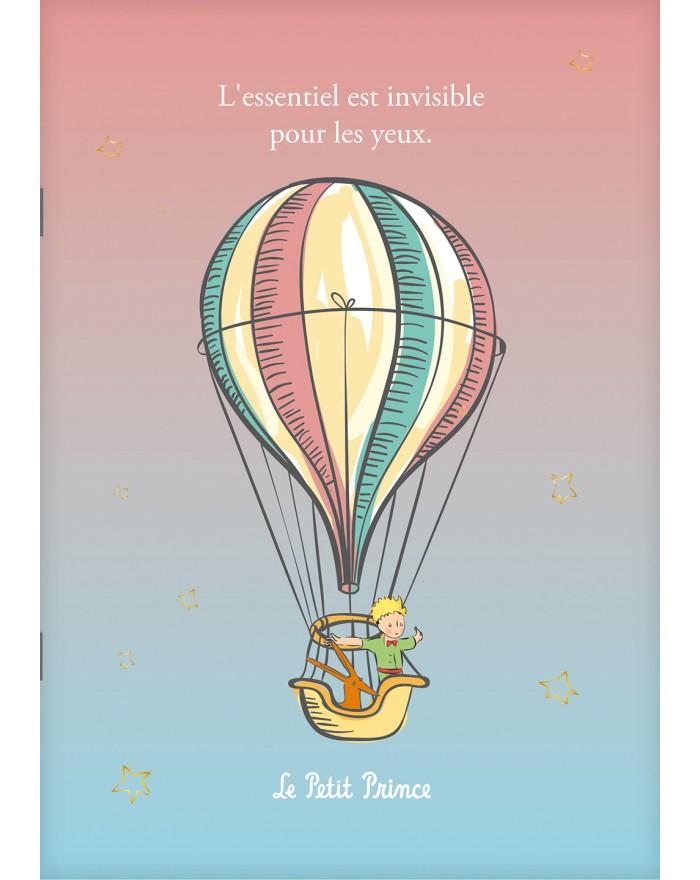

As I sat pondering upon what knowledge is, I was immediately reminded of a powerful anecdote from The Little Prince, an extremely influential French novella penned by Antoine de Saint Exupéry.

The book contained an image (perhaps one of the most famous in world literature) and asked the reader to ponder upon what it was. At first glance, many readers would agree that the image was that of a hat. However, the author argues that it could very well also be a boa constrictor that had swallowed an elephant whole. I shall reference this allegory in the subsequent sections of this essay.

I believe that the Universe and the Truth that is associated with it is nothing but utter, absolute chaos. Knowledge to me is simply a proxy; a tool that we think allows us to infer truth about the Universe. And while knowledge does succeed in making sense of some parts of the Universe, there always comes a time when it fails to explain something and descends into futility.

I shall try to demonstrate the above statements using an allegory. Imagine that you are lying on the grass and you see a cloud in the shape of an elephant. The fact that you see an elephant in the cloud is like knowledge. The cloud is the truth. While the shape of the cloud is chaotic and inherently random, you try to build a model of an elephant around its shape in order to explain it and/or understand it better even though nature never intended for that to happen.

Therefore, the creation and pursuance of knowledge is nothing but a never-ending quest to form proxies that would help understand the Universe a little ‘better’ than what previous proxies could do. Ever since mankind was given the gift of sentience, it has indulged in an almost insurmountable quest of making sense of the chaos in the midst in which it found itself in.

The first humans were perplexed by phenomena such as lightning, rain, the stars and the endless cycle of day and nights. In its quest to make sense and gain knowledge of what was going around, mankind developed its first proxy: God. Alexander Drake, in his treatise The Invention of Religion, has argued that any sentient being when placed in an environment of zero knowledge will firstly and eventually develop the concept of God in order to explain phenomena that surrounds him/her.

However, mankind soon realized that the concept of an omnipotent being responsible for everything that surrounded them had its shortcomings. While it performed a satisfactory job of explaining events that had already occurred, it fell extremely short of predicting outcomes around circumstances that were extremely similar. And it is in this shortcoming that we see the genesis of science.

Although science understandably enjoys intellectual hegemony over religion, at its core, the two attempt at doing the same thing: making sense of the Universe. Science tends to enjoy superiority on account of its modeling prowess and predictability. For instance, when the laws of motion were formulated by Newton, it was possible to compute the velocity with which a ball would land if it fell from a certain height. This was true of every ball and every setting as long as the height remained the same. However, we often misjudge this discovery as ‘truth’. Scientific models were never the absolute truth. They were just proxies that explained a certain behavior of the Universe accurately. They were like the elephant in the clouds. The Universe simply does not care for scientific or mathematical laws. It isn’t aware of the laws of motion. It just so happens that in its chaos, we manage to sometimes find apparent order in it.

Since, by its very nature, knowledge is nothing but a collection of proxies, it always tends to break after a certain point of time. As an illustration, consider the evolution of the structure of the atom. In the beginning, it was believed that an atom was a blob of positive charge with negative electrons embedded in it. All phenomena observed in association with the atom could be explained by this model. But then came a period when something else about the atom was observed. The cloud did not look like an elephant anymore. So, now it was postulated that an atom was mostly empty space with a dense, positive nucleus at the center and negative electrons revolving around it. This model, in turn, was rendered useless when quantum mechanics was discovered.

Thus, we see that knowledge and its acquisition is merely the development of proxies that we presume are better on account of its potency to explain more facts about the Universe than its predecessors. The scientific world has a current set of proxies with which it understands the world. However, it is an absolute certainty that some phenomena will be eventually discovered that will render it impotent.

Now that we’ve established that knowledge is nothing but a proxy to create order out of something that is inherently chaotic, development of knowledge is simply an exercise of developing apparently more ‘potent’ proxies over existing proxies. Understandably, there is always a base set that arises out of nothing. In this essay, I will refer to these points of knowledge as axioms (akin to Mathematics). These are ‘facts’ that cannot be proved and are assumed to be the truth. All knowledge is built from this base set of axioms.

The potency of knowledge is constantly tested by ensuring it is consonant with the phenomena that it attempts to explain. Once it fails to explain something, it must be either discarded or modified in order to explain the aforementioned phenomena and still maintain consonance with everything that it has correctly explained before.

Some knowledge is created by the easy modification of the current state of knowledge. An example of this is the evolution of Rutherford’s nucleo-centric model from Thomson’s positive blob. Some knowledge, on the other hand, requires a modification of the base axioms in order for it to come into existence. For instance, atoms were considered to be matter. This was considered base truth. However, when quantum mechanics emerged, this axiom had to be discarded in order to make room for the duality notion. It is at this point that I make a reference to the Little Prince hat. Knowledge to me is like that har. It is constantly changing and is never a reflection of absolute truth. For all we know, the shape drawn above is just a random collection of lines. Our observations and existing notions (knowledge) lead us to believe that it is a hat. However, should we see this hat starting to slither, we will evolve our understanding to label it as a boa constrictor that has swallowed an elephant. In the future, we may observe some other things that may not be cognizant with this model either. Then again, we will attempt at describing it as something that explains that particular phenomenon in addition to everything that was observed earlier.

With my thoughts on knowledge substantiated, I shall now turn my attention to what it is I know. If by the term ‘know’, I’m referring to the absolute truths about the Universe, I find it necessary to quote Socrates in saying that I know nothing. All I have with me is a set of useful proxies that allow me to make sense out of some components of the Universe I exist in. I am cognizant of the fact that they may be proved wrong in the future but so far, they have helped me in explaining everything that I have observed and/or experienced.

In the same breath, I would, therefore, say that my conquest of knowledge is simply the acquisition and development of better proxies that enable me to understand a superset of the components of the Universe that my present state of knowledge may fail to explain.

A stated several times in this essay since knowledge is nothing but a set of proxies, the question begs as to how do we actually develop these proxies. We do so by interaction and observation. We observe something that is happening in the Universe and try to construct causal reasoning behind it. If the reasoning (or model) holds for subsequent events of the same nature, it survives for the time being. If it doesn’t, the model is modified. In some other instances, we supply a stimulus and record the response. We observe how responses differ to different stimuli and again, we try and construct a model that is potent enough to extrapolate on stimuli-response pairs that haven’t been explicitly tested before. This relationship between stimuli and its corresponding stimuli is again something we construct. It doesn’t inherently exist. As before, it is like the elephant in the cloud.

If I am made aware of something that I do not ‘know’, it could mean one of two things. Either I do not have a proxy in my set of proxies that can help me understand it. Or I possess a proxy that had given me an incorrect result. In the first case, I simply add the state of the art proxy to my set and in the latter, I modify my existing proxy using techniques that I have explained above. There are several instances where the latter might cause cognitive dissonance in my head. In other words, the modification of a particular proxy threatens the existence of the other proxies. In such cases. I make a cost-benefit analysis. There is never a right answer to this question. It boils down to which I would consider being more taxing to my mental and ethical well being: the ignorance of one phenomenon that my premature proxy cannot explain or a major overhaul of my entire set of proxies altogether.

In the final sections of the essay, I will attempt at creating a narrating around me knowing my self. I have come to understand that there are four components to knowing me. The first is observations and a set of associated explanations that are public knowledge to me as well as others around me. The second are those that are known to me but not to others. The third is vice versa. The fourth and the final are things that are not known by anyone.

I have come to realize that I will never come to know the absolute truth about myself. In that sense, I am like the Universe in which I reside. I can only create proxies that help me to understand a component of myself better. The truth about me resides in the fourth component. The other three are merely observations and proxies created on account of it. There are things that I believe are true about myself. There are certain moral principles that I believe I adhere to. But I am cognizant of the fact that these may all be rendered false when I’m put in a situation that forces me to alter my vision of myself. I will never know who I truly am. I will only know parts of me as I progress through life that will hold true until they are broken under certain circumstances. In my pure essence, I am chaos. There is no inherent order to who I am. I can only run with assumptions and be resilient when faced with the prospect of changing my perspective of myself.