Disclaimer: This post is part of a series of essays I wrote at the Young India Fellowship. This particular essay was written as a transcript as part of the course titled Totalitarian Century.

“Someone must have falsely denounced Josef K., for without having done anything wrong, he was arrested one morning.”: The Trial, Franz Kafka

The opening lines of Franz Kafka’s The Trial is one of the most chilling and memorable of all time. A well-established chief banker, Josef K. is suddenly arrested one day by unidentified agents from an unidentified organization for committing an unidentified crime. What follows is a host of absurdities: the guilt of the protagonist is assumed, he is allowed to roam free despite being ‘under arrest’, trial processes take place in shady attics and the convicted (and the reader) has absolutely no idea of the crime he has committed throughout the entire novel.

As with his other works such as The Castle and Metamorphosis, Kafka’s magnum opus has been subject to a variety of interpretations ranging from psychoanalytical to religious to political. Kafka was a German Jew and there is evidence that suggests that he was deeply influenced by the Anti-Semitic Trials that took place in Hungary, France, and Czechoslovakia in the late 19th century. This, combined with the tensions and rise of totalitarian states in Europe prompted Kafka to write his novel just before the outbreak of the First World War.

In the novel, Kafka states quite clearly that Josef K. lives in a society with a legal constitution, universal peace and enforceable law. Nevertheless, he gets arrested for a crime he doesn’t know he committed and is given little to no legal assistance or context by the state. He also goes through a thoroughly unfair trial and is brutally executed in the end screaming “Like a dog!”. Franz Kafka died in 1924 and little did he know that his absurdist novel would become reality in his country barely a decade after his death.

When Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party assumed power, they promised to resurrect Germany from its defeat in the First World War and establish a Reich that would last a thousand years. The Nazis were also morbidly obsessed with eugenics and believed that their race, the Aryans, was the master human race. Other lower races, especially the Jews, had to be eliminated to ‘purify’ the human race and make them pay for the crimes they had committed against the state, which was directly responsible for the defeat of Germany in the First World War.

By the late 1940s, hundreds of thousands of Josef K.’s were met by Nazi agents at their doors and were arrested despite not having done anything wrong. Their assets were seized and they were sent to concentration camps without any trial where they faced torture and almost certain death. In other words, they died ‘like a dog’. Der Prozess had become an undeniable reality.

The Nazi Holocaust, although an extreme event, is unfortunately not an exception. Millions of Josef K.’s have died since 1945 in the USSR, Rwanda, and Armenia. All these countries had a constitution and a notion of justice in place. The Trial was most definitely Kafka’s warning about totalitarian regimes. It is fitting that he chose not to disclose the surname of the protagonist. It was his way of saying that this man could be anyone: a Jew in Nazi Germany, a Rohingya Muslim in present-day Myanmar or a Viet in Cambodia in 1975.

So far, this essay has created analogies between The Trial and historical events with the assumption that the protagonist of the story hadn’t done anything which could be considered a crime. The remainder of this essay will have a slightly different take: What if the protagonist had indeed committed ‘a crime’ and simply didn’t know he did?

By now, history has an extremely rich archive of the totalitarian states that have existed (or exist) around the world. Most of these states have very similar characteristics: fervent nationalism, a powerful tyrant dictator, rampant jingoism and tendency to commit genocide of minority and disadvantaged groups.

However, there is a new kind of totalitarian state brewing. Its primary weapon is not massive armies or concentration camps but data; extensive information that it collects about its citizens from every imaginable aspect of their lives. It is unlikely that Kafka had the clairvoyance to predict data-driven totalitarian states in the 21st century but nevertheless, his book manages to serve as a chilling warning to this nouveau totalitarianism too.

In 2016, the Netflix series Black Mirror released an episode titled Nosedive. True to its theme, it features a dystopian world where people were required to rate other people based on the quality of interactions they had with them. Based on the ratings other people gave you, you would be assigned a social credit score. This score was as important as money as it determined the kind of public places you could visit, homes you could rent and neighborhoods you could live in.

On the outset, this episode may seem like science fiction but a state like this is actually taking shape in the People’s Republic of China. China announced that it was experimenting with a social credit system that could determine the kind of loans you could avail and jobs you could take. Traditionally private information such as shopping history and friendships of an individual could now be made public. The Chinese Government claimed that it was to build a system of trust but the underlying repercussions of this system are immense. This system is the first step towards total surveillance. The effects have already begun to seep through. For instance, a number of students in China were barred from admissions in schools and colleges on account of their parents’ low credit scores. The parents were apparently on a ‘national blacklist’. Josef K. had once again faced consequences without having done anything wrong and without knowing the nature of his crime.

Another interesting facet of Josef K.’s trial was his freedom of mobility. Despite being under arrest, he is allowed to roam freely and conduct his business as usual. This is because the unidentified authority that has charged him has means and tools at its disposal that allows it to identify the location of Josef K. at any given time. Many countries in the west have tools that enable them to track people’s locations and they have misused severely by authorities. For instance, authorities at a local police department in the US were found guilty of using traffic light tapes to identify cars parked outside of gay bars and blackmail the owners into revealing their sexuality to their family. China is also undertaking a project of supplying its police force with AR spectacles that would automatically identify a person. Therefore, the surveillance aspect of The Trial is not science fiction anymore; it is slowly becoming a disturbing reality.

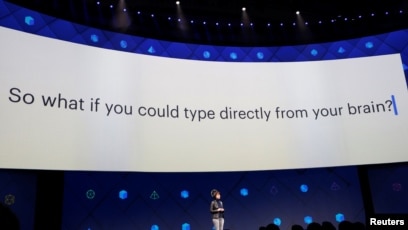

Throughout the novel, we do not have any idea of the nature of crimes that Josef K. has committed. And neither does Josef K. himself. But can this be possible? To answer this question, this essay will devise a thought experiment that borrows elements from George Orwell’s dystopian novel, 1984. In 1984, there is a separate class of crime called ‘Thoughtcrime’ which is the crime of having thoughts considered ‘illegal’. The Big Brother in the novel takes elaborate steps to ensure no one is committing this crime but recent development in technology might make this process much easier.

Neuroscientists and major Software Giants (including Facebook) are developing a technology that can directly convert thoughts to speech or text. Considering the fact that this technology will be embedded into wearable devices, this has the potential to give the provider unlimited access to our thoughts. The question, therefore, begs to be asked. What if totalitarian governments used this technology to read the thoughts of its citizens and incarcerate those that harbored thoughts that were considered dangerous? Then, we would finally have the answer to The Trial’s most burning question. Josef K. of the 21st century had harbored a thought that made it eligible to be considered as Thoughtcrime. Unbeknownst to him, this thought was recorded on his wearable device and transmitted to the Government. The Government then arrested Josef K. without giving him any explanations regarding the circumstances.

Dystopian novels have been revered as being important hallmarks of literature but we often ignore the salient warnings they give out. The Trial is no exception. Despite its ‘validation’ from history, readers will still find the piece to be absurd. But the warnings that it gives out must be taken seriously. It may not be very long before we too have agents outside our door waiting to arrest us, deny us a fair trial and execute us like dogs.

Bibliography

- Mitchell, M., & Kafka, F. (2009). The Trial (Oxford World’s Classics). Oxford University Press.

- Translating Kafka. (n.d.). Kafka Translated: How Translators Have Shaped Our Reading of Kafka. doi:10.5040/9781472543653.ch-001

- Löwy, Michael (2009) “Franz Kafka’s Trial and the Anti-Semitic Trials of His Time,” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 13.

- Taylor, A. (2015, April 24). It wasn’t just the Armenians: The other 20th century massacres we ignore. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/04/24/it-wasnt-just-the-armenians-the-other-20th-century-massacres-we-ignore/?utm_term=.db4f1f125afa

- Zaretsky, R. (2014, April 28). 100 Years Later, Revisiting Franz Kafka’s ‘The Trial’ and World War I. Retrieved from https://forward.com/culture/196986/100-years-later-revisiting-franz-kafkas-the-trial/

- Reisener, M. (2018, February 24). Does Kafka’s ‘The Trial’ Have Lessons for Today? Retrieved from https://nationalinterest.org/feature/does-kafkas-the-trial-have-lessons-today-24632

- Song, B. (2018, November 29). The West may be wrong about China’s social credit system. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/theworldpost/wp/2018/11/29/social-credit/?utm_term=.66377863d9a4

- Death by data: How Kafka’s The Trial prefigured the nightmare of the modern surveillance state. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.newstatesman.com/2014/01/death-data-how-kafkas-trial-prefigured-nightmare-modern-surveillance-state

- Marr, B. (2019, January 21). Chinese Social Credit Score: Utopian Big Data Bliss Or Black Mirror On Steroids? Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2019/01/21/chinese-social-credit-score-utopian-big-data-bliss-or-black-mirror-on-steroids/#40b32d1748b8

- Brooker, C. (Writer). (n.d.). Nosedive [Black Mirror]. Retrieved from https://www.netflix.com/watch/80104627

- Kobie, N. (2019, January 24). The complicated truth about China’s social credit system. Retrieved from https://www.wired.co.uk/article/china-social-credit-system-explained

- Guenther FH, Brumberg JS, Wright EJ, Nieto-Castanon A, Tourville JA, et al. (2009) A Wireless Brain-Machine Interface for Real-Time Speech Synthesis. PLoS ONE 4(12): e8218. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008218

- Church, M. (1956). Time and Reality in Kafka’s The Trial and The Castle. Twentieth Century Literature, 2(2), 62-69. doi:10.2307/440948

- Liao, S. (2018, March 12). Chinese police are expanding facial recognition sunglasses program. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2018/3/12/17110636/china-police-facial-recognition-sunglasses-surveillance

- Orwell, G. (2014). 1984. New York, NY: Spark Publishing.