Disclaimer: This post is part of a series of essays I wrote at the Young India Fellowship. This particular essay was written as a final paper for the course Kabir: The Poet of Vernacular Modernity.

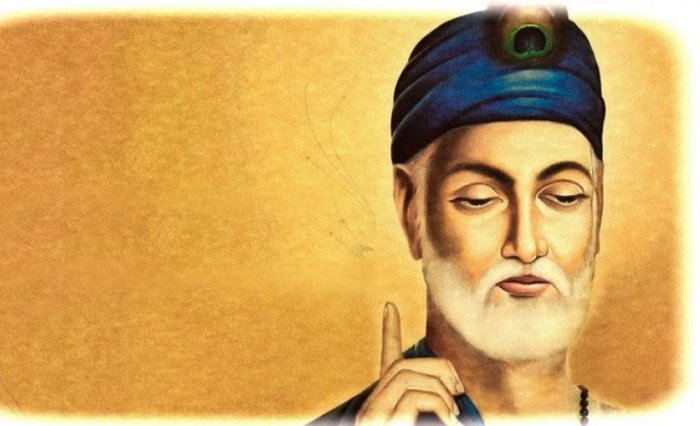

The premise of this essay is to discern if all the works attributed to the saint, reformer and poet Kabir were written (or enunciated) by one person or if there is a possibility that the name ‘Kabir’ was a pseudonym used by multiple poets to broadcast their views between the 14th and 16th century.

The essay argues that the former is more likely. In other words, although historical evidence suggests that a weaver poet named Kabir did live in Benaras somewhere in the 15th century, the works attributed to him were not his original work alone.

The first argument relates to the exact timeline of Kabir’s life. To date, there is not enough historical evidence that puts this matter to rest. Mentions of Kabir can be found from as early as the starting of the 14th century to as late as the end of the 16th. In his book Kabir, Prabhakar Machwe gives us the wildly different timelines that have been proposed. The most widely held view, as purported by Kabir Charith Bodh, was that Kabir was born in 1398. However, in his work Khajinat-ul-Asafiya, Maulvi Ghulam insists that Kabir was born in 1594, two full centuries after the date suggested by Kabit Charith Bodh. But more than his birth, it is the year of his demise that is more hotly contested. A certain sect of scholars believe the date to be somewhere between 1448 and 1450. In fact, the Archaeological Society of India has suggested that a tomb of Kabir was built somewhere during 1450.

However, this date of 1448 is rejected by other sects of scholars who believe Kabir was a contemporary of Sikander Lodi, a sultan who ruled Delhi between 1489 and 1517 and visited Kashi in 1494. A death in 1448 would not have made the fabled meeting between the two possible. The Ain-e-Akbari, a pivotal historical work published in 1596 by Abu Fazl also mentions Kabir as one of the great poets who is no longer alive.

Finally, there is a ‘middle-man’ view which suggests that Kabir lived through it all, between 1398 and 1518 to a ripe old age of 120. A possible reason for such immense confusion in his timeline could be because poetry in his name was being propagated and produced throughout this period of more than a century which led different people to believe that Kabir was alive at a different point of time. It is extremely unlikely that a man in the 15th century survived to the age of 120. What is more likely is that a group of poets published and produced poetry under the pseudonym Kabir over this very long timeline.

The second argument is that of Language. Kabir is extremely well known for rejecting the polished languages of Hindi and Persian in favor of a language more understandable to the masses; a language alluded to as Saddhukari by modern scholars. However, Kabir’s poetry is riddled with several languages. In Linda Hess’ The Bijak of Kabir and Prabhakar Machwe’s Kabir, this fact is alluded to in detail. His poems seem to have traces of Hindi, Persian, Marwari, Urdu, and Bengali. Additionally, there is evidence which suggests that his language style tends to change with the subject matter and does not have one particular style (that most other poets spend a lifetime to carve).

These facts can be used to postulate a very likely scenario: it is possible that several poets lived in several different regions and wrote on several different topics. Each poet had a distinct voice of his/her own and had issues and topics that s/he deeply cared about. However, they all came to use the pseudonym of Kabir as their signature. Therefore, the richness and diversity of language and the style of language being dependent on the topic.

The third argument is that of Women. Kabir’s views on femininity remain one of the most controversial facets of the poet. Kabir is known to have been extremely vocal about his condemnation and denunciation of women. His seemingly misogynistic attitude is however not an anomaly amongst the great poets of the world. In his Thus Spake Zarathustra, the German Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche famously wrote:

Everything about women is a riddle and everything about woman has one solution: it’s called pregnancy.

Kabir’s views were far stronger and far more blasphemous. For instance, one of Kabir’s couplets goes as follows:

Kabit naari parai apni, bhugtya narakahi jaye,

Aag aag sab ek hai, tamain haat na baahi

Translated by Gupta in 1986, this translates to:

Kabir says he who associates with a woman, whether his own or another’s, is going to hell

All fires are one; so don’t burn your hands in it.

Modern scholars argue that Kabir isn’t speaking against women in his poetry but is merely using women as a metaphor for all that is wrong and evil and unjust with the world.

This point of view would have been acceptable if not for another facet of Kabir: his love and eroticism for his God, Rama. As stated by Purushottam Agarwal in his essay The Erotic to the Divine: Kabir’s Notion of Love and Femininity, there are over 270 verses in which Kabir exhibits eroticism and a poignant desire to become one with his God. Furthermore, he does so by assuming the form of a woman. Assuming that Kabir had no qualms regarding homosexuality, it seems apparent that he believed that he could only make true love to his God by adopting the form of a woman. This, in turn, alludes to the fact that Kabir believed that the epitome of sexual desire and fulfillment, of unconditional and intense love, of devotion, could only be achieved by the feminine. The female was more capable of giving love to the male than the vice versa.

It is in these two aforementioned facts that lie the greatest contradiction and paradox regarding the poet. On one hand, he uses women as a symbol of all that is evil and unjust with the world and strongly denounces any form of interaction or contact with it. On the other hand, he becomes a female and asks the male God to become one with her. Even if we assume that Kabir’s usage of femininity is metaphorical, it is astounding that he would use the same metaphor to denote two completely contrasting ideas.

As with the previous two arguments, this contradiction can be fixed if we assume that the works are by separate poets. One poet used femininity as a metaphor for evil. The other used it as the epitome of love, desire and affection to God.

A related question could be: why does Kabir find a need to convert to the female form to show his love for God? Why doesn’t he make God female instead? While the explanation that the woman is a metaphor for the zenith of love, affection, and desire is convincing, we should not rule out another equally plausible explanation: the existence of a female poet writing under the pseudonym of Kabir. Why a female poet would do is extremely obvious and has been brilliantly elucidated by Virginia Woolf in her essay, If Shakespeare Had A Sister. If this were indeed the works of a woman, it would have been very unlikely that it would have reached the levels of popularity they enjoy to this day. Combine this with the fact that a woman expressing her erotic desires would have been extremely taboo in the conservative 15th century India. The Bhakti poet Meera did but she lost all her material possessions in the process. In other words, there was plenty of incentive to write under the pseudonym of a famous male poet.

Thus far, this paper has discussed certain facts about Kabir that hint at the possibility of the existence of multiple poets rather than one. The rest of this paper will focus on plausible reasons as to why there was an incentive to do such a thing.

The premise of multiple poets writing under one common pseudonym is not a new idea. It has also been proposed in relation to probably the greatest poet of all time, William Shakespeare. There are some startling similarities between the two giants. Both were born into illiterate households. There is historical evidence suggesting that Shakespeare’s father and son were both illiterate. It seems highly unlikely that the intermediate generation reached the epitome of literacy. Secondly, there are the circumstances surrounding his death. He makes no mention of his books, plays or poems in his will or his documents. The only theatrical references were interlined in his will which cast deep suspicion on the authenticity of his requests. Diana Price, in her essay Reconsidering Shakespeare’s Monument, argues that Shakespeare’s works were authored by aristocrats such as Derby and Oxford under the pseudonym and they did so to bypass the “stigma of print”, a convention that restricted works by aristocrats to be published only in private circles and not be made available to the public. Another reason may have been because Shakespeare’s plays clearly advocate a Republican form of government and therefore its author was always at risk of being prosecuted by the monarchy.

The aforementioned point finds a great amount of relevance in the context of Kabir. Kabir’s poetry contained vast amounts of criticism for every major religion that existed in the subcontinent in the 15th century, be it Hinduism, Islam or Buddhism. Criticism of religious beliefs and thoughts do not go down well even in the 21st century so one can imagine the magnitude of possible repercussions five centuries ago. Writing under the pseudonym of Kabir, a lower caste, illiterate Muslim weaver was the perfect deception. It would have helped all these poets with blasphemous views find a voice without facing the risk of prosecution.

With time, it is possible that the name of Kabir became synonymous with rational thought, the denunciation of any form of God and a rejection of irrational practices of Hinduism and Islam. In such a scenario, it made even more sense to continue using the name of Kabir long after the original weaver was dead. Kabir, in this way, becomes a symbol.

In conclusion, this essay does not reject the existence of a weaver-poet named Kabir. It is very likely that such a person did exist. But what is equally likely is the possibility that all works written in his name were not written by one person. They were written by poets in different regions in different languages advocating different thoughts. Kabir, therefore, was more of a symbol; an amalgamation of revolutionary thoughts and the epitome of South Asian Literature between the 14th and the 16th centuries.

References

- Hess, L. & Singh, S. (Tr.) (1986) The Bijak of Kabir

- Agrawal, P. (2011) The Erotic to the Divine: Kabir’s Notion of Love and Femininity

- Machwe, P. (1968) Kabir

- Woolf, V. (1929) A Room of One’s Own

- Price, D. (1997) Reconsidering Shakespeare’s Monument

- Agrawal, P. (2004) Thematology: Seeking an Alternative to Religion Itself